This post is by Guy Shrubsole.

Rifling through boxes of old postcards in junk shops is, admittedly, not my coolest pastime. But it’s something I’ve started doing of late, because some of them can provide crucial clues to the destruction of our chalk downland.

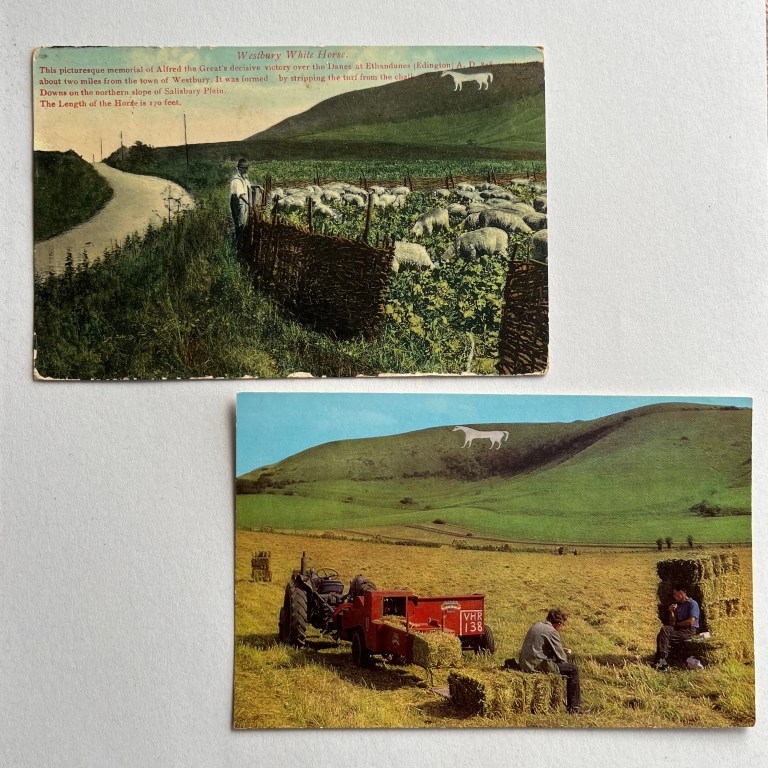

Here’s an example: two postcards I found in a collector’s shop in Salisbury, taken in different time periods, but both showing the unmistakeable outline of the Westbury White Horse:

From the size and placement of the chalk figure, we can match them up and see that both postcards were photographed in almost exactly the same place. But they reveal big changes in agriculture. The first shows a flock of sheep grazing on brassicas amidst hazel hurdles (fencing made out of woven hazel). In the second, the sheep have gone, to be replaced by a hayfield recently cut and baled by machine.

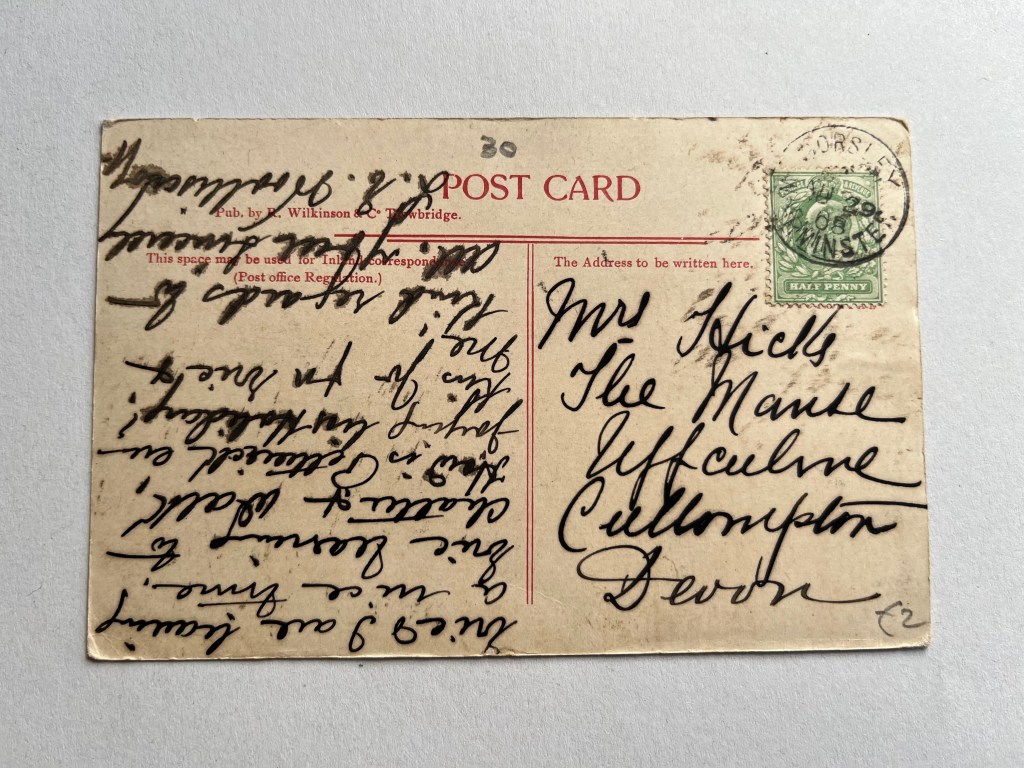

Turning the postcards over, we can have a go at dating them. The first one is easy: the stamp bears the head of King Edward VII, with a postmark of 1908. The second is unposted and harder to accurately date, but is clearly more recent. A few clues help us pin it down a bit: some other examples of this postcard for sale on eBay all have Queen Elizabeth-era stamps. And a closer inspection of the baling machine reveals it to be a Jones Minor Baler, first manufactured in the 1950s.

What we have here, then, are two snapshots in time revealing a seismic change in the agriculture and ecology of the chalk downs. In the Edwardian era, the land around the Westbury White Horse was still dominated by sheep farming. In the summer, shepherds grazed their flocks on the chalk downland by day and then folded them onto the lower slopes by night, where they fertilised the fields (a practice sometimes called transhumance).

This fertility cycle was broken during and after the Second World War, when mechanisation and a drive to grow more wheat saw many downland areas ploughed. The old system of transhumance disappeared as artificial fertilisers replaced sheep. This is the world we see in the second postcard. (In this example, the hay is feed for livestock; in many other parts of the chalk downland, pasture was ploughed for wheat and barley.)

Do you have any old postcards showing what the chalk downs looked like in the past, or showing changes to their ecology over time? Please get in touch and share them if so! You can get in touch via: ghostsofchalkcountry [at] gmail.com.